Philanthropy

Charitable Gifts in 2020 Funded by Depreciated Securities.

Why would a donor consider using depreciated securities to make a charitable contribution this year? After all, such assets are not typically thought of as a good asset for charitable giving.

But this is not a typical year.

The use of depreciated securities may be just the right idea this year when donors plan for their charitable giving. In the currently volatile economic market, many investors are experiencing a depreciation in the value of some (if not all) of their stock holdings. Charitable giving offers a way to optimize the value of depreciated securities.

Here’s why: Unlike gifts of appreciated securities – which create a charitable contribution tax deduction and allow the donor to avoid taxation on the gain in value – gifts of depreciated securities create a capital loss (that can offset capital gains) and the opportunity for a charitable contribution deduction.

Here’s how:

- The donor sells securities that have been held for more than a year and have lost value since being acquired.

- The donor then uses the proceeds from the sale to make the charitable contribution.

- This two-step sequence allows the donor to take a capital loss on the sale of the depreciated securities and a tax deduction on the charitable gift.

While tax considerations may not be the number one reason most donors make charitable gifts, the tax-wise aspects of this strategy can be substantial. Let’s say the donor bought 1,000 shares of a stock in 2018 at $60 per share. The stock is now trading at $25. A sale of the stock yields $25,000 in cash and a $35,000 capital loss. The $25,000 can be used to fund a charitable contribution. And, this year, under the Cares Act, the donor can deduct charitable giving up to 100% of Adjusted Gross Income.

Whether the donor plans to make an Annual Fund gift or a payment on a campaign pledge, the use of depreciated securities may be a strategy to consider in 2020.

“What a year this week has been.”

Lizz Helmsen

Managing Director

This is how a friend of mine described the experience of reuniting with his fiancé in Canada and then getting back to the U.S. as travel restrictions were being put into place, and it’s turning into a common phrase in our new Covid-19 era.

Fundraisers are strong, capable, passionate, well-educated, Type A people. But we’re not immune to the stress that is so prevalent today. In fact, being strong, capable, passionate, etc. actually makes us more susceptible to anxiety in many ways, in no small part because we feel responsible for our organizations’ missions.

There are many resources available right now that talk about how to fundraise during difficult times (and about why it’s absolutely crucial for you to keep going!). But we also need to take care of ourselves. A good first step is to remember that we’re not alone. Increasingly, prompted by the World Health Organization and others, the term “physical distancing” is replacing “social distancing”. This is an important distinction, and one fundraisers inherently understand: relationships matter.

We also know the power of storytelling. Lessons that come from stories are particularly powerful. Plus, while experience is the best teacher, you don’t always have to be the one learning the lesson directly. With that in mind, here are some of the stories I remember when I need a boost.

There Are No New Plots – Only New Twists

This comes from my high school drama teacher. Yes, we are facing a global crisis. And the double-whammy of the pandemic and resulting economic stress is one heck of a plot twist. But we have been through crises before, even multifaceted crises including the 1918 flu pandemic that coincided with World War I. We will get through this.

Understanding that there are no new plots can also help when we feel pressure to come up with something super-creative/different/inspiring. No. We don’t have to do something earth-shattering. We just have to be sincere. None of what I’m saying here is revolutionary, but I do hope that I have enough of a new twist to be of use. As an added bonus, when we do have a brilliant idea, we can recognize (and be grateful for) all of the bits and pieces from yesterday’s plots that we combined to move forward.

Panic – Then Get Over It

This comes from a guest professor in college, and it seems counterintuitive. Who in their right mind would actually encourage panic? Especially right now. But I still remember how he walked into class, introduced himself, and then gave us a project that was an order of magnitude larger than anything we had done to date. Before we could hyperventilate, he told us that most people’s advice would be to not panic, but that wasn’t realistic. It’s human nature to panic when faced with something overwhelming, so go ahead. Give yourself a moment to let it out rather than holding it in and letting it fester. Then take a deep breath. Get over it. Start planning. This is the less clinical way of explaining why repression is so damaging to our mental health.

Of course, panic doesn’t always hit immediately. Sometimes we’re doing just fine right up until the point where we’re NOT fine. One of the school counselors I know says that week three of a new school year is when she usually starts seeing problems for students because the newness is gone and reality sets in. Personally, I tend to get nervous after I’ve finished something, when the adrenaline wears off and the “If Onlys” start: “If only I’d said/done this differently,” or “I should have done xyz.” Regardless of when anxiety strikes, the answer is still to acknowledge that fear is normal but we don’t have to let it control us. Take a deep breath. Get over it. Start again.

Always Look on the Bright Side of Life

Yes, I am a Monty Python fan. And while the reference – like much of Monty Python – is irreverent to say the least, it’s good advice. When I heard my son quote Holy Grail during one of his darkest days, that glimpse of humor was something to hold onto. My friend who had the harrowing week that led him back to the U.S.? He and his fiancé got married and are together. Some silver linings are small. My dog has never been happier. Some may have long-term effects that you can’t see yet. Family dinners are, by default, happening more frequently, and studies consistently show that students who have family meals do better academically, have stronger relationships, engage in fewer risky behaviors, and even have greater vocabularies.

One of the great benefits – and true joys – of being a consultant is that I have a front row seat to watch remarkable organizations across the world as they pivot to address the current crisis, stay connected with their constituents, and continue advancing their missions. I say this not to minimize the challenges we face – they are real and daunting – but to acknowledge the awe-inspiring efforts of people who are dedicated to fulfilling their missions regardless of what the world throws at us.

Here are two of my silver linings:

- A youth orchestra had their much-anticipated trip to Carnegie Hall cancelled, along with all of their live rehearsals and their additional spring performance. This was a huge blow, especially for the high school seniors. But the whole organization stuck together and quickly rallied around three virtual goals: Musical Growth, Staying Connected, and Staying Live with Music. They’re now holding virtual masterclasses once a week, using Acapella app for students to make recordings, and planning for virtual auditions should that be necessary. Parent and student feedback has been tremendous.

- Another youth organization reached out to one of their lead donors with the authentic purpose of telling him what the organization was doing, how they were pivoting to continue serving children. The Board wanted to keep their staff, knowing that staff is the lifeblood of their mission. The donor asked how much it cost per month to keep everyone employed. Not knowing where the question was leading, the executive director hesitated but chose to respond honestly. The donor said, “How about I cover three months of that expense for you.” What a wonderful, powerful example for all of us: transparency, mutual respect, and a donor jumping at the chance to help!

“Real Strength Has to Do with Helping Others”

Having lived in Pittsburgh for 30 years, I’d be remiss if I didn’t think of Fred Rogers. When I’m feeling cynical, my favorite book is a compilation of famous insults. The old Scottish curse, “May you live in interesting times,” seems particularly apropos at the moment. But Mr. Rogers’ sense of calm and his love are always here for us, and his words are stronger than even the cleverest bit of snark. We are all connected, all neighbors, all capable of giving and worthy of receiving help.

So, as we navigate uncertain waters, remember that you are not alone. You can do it. We will help.

Where are YOU sitting? With a nice girl or on a hot stove?

Albert Einstein once said, “When you sit with a nice girl for two hours, you think it’s only a minute. But when you sit on a hot stove for a minute, you think it is two hours.”

These days, I think lots of people are looking for a nice place to sit where they can use their experience and education and find enjoyment.

Fundraisers and philanthropists are no different.

Rather than folding up your fundraising efforts during this pandemic, why not turn it into an opportunity to help others find their strengths, connect with your mission and make a difference. You might learn something about yourself in the process.

It’s a good bet that prior to March, you never heard the phrase shelter at home, let alone thought it would ever apply to you. Now we’re in the middle of this new normal with a target end-date that moves as quickly as COVID-19 seems to spread.

It’s a good bet that prior to March, you never heard the phrase shelter at home, let alone thought it would ever apply to you. Now we’re in the middle of this new normal with a target end-date that moves as quickly as COVID-19 seems to spread.

The situation has me thinking about how different shelter at home must be for each of us.

I live in the middle of 12 acres of woods with plenty of room to roam without ever getting close to a neighbor. My friends in larger cities don’t have that same luxury; their lives look entirely different. The definition of “home” is so deeply personal, even people living in the same house might have vastly different images.

In the mid-1990s, I found new context for my definition of “home” while serving as fundraising counsel for Habitat for Humanity International’s first large-scale capital campaign. Now, as I advise my current nonprofit partners in responding to COVID-19, I find myself leaning on those valuable lessons.

First, a simple, decent and safe home makes a world of difference, especially children who need this to thrive. During this crisis, it’s more important than ever that organizations serving the homeless children share their message. Make sure your communities know your services are continuing and are critical for ensuring defenseless children have the same opportunity as the rest of us to safely shelter at home.

In fact, no matter what your organization’s mission, DO NOT STOP fundraising. Be empathetic to what your donors are experiencing while also being clear and concise about your organization’s needs. It’s our job to let people know how they can help, not make the decision for them.

Second, celebrate the fact that you help people when you give them the chance to help, and for some that means making a charitable gift. Habitat for Humanity’s model puts the recipients of philanthropy working alongside the philanthropist. Most of the philanthropists will tell you they feel they received much more from the experience than they contributed, including the lifelong lesson that “giving is at the heart of living.” The opportunity to give lifts spirits and gives deeper meaning to the life of the donor. As a fundraiser, you are the conduit that connects people to the causes they care about most.

Third, not everyone can be a nurse who helps the sick, an electrician who wires a house or a plumber who fixes a leaky faucet. But just because you’re good at something, doesn’t mean it brings you joy. As a classic overachiever, there are many things I do well that I simply do not enjoy; paperwork and book-keeping are classic examples!

A few years ago, I was introduced to Marcus Buckingham’s work on “Strength-Based Team Development” (https://youtu.be/czsEJGJnPAY), and it dramatically changed what I consider my strengths. Marcus suggests that what you are good at is an ability, but a strength is something that makes you stronger.

In my experience, this especially applies to fundraising professionals who often wear many hats, some of which are important to raising money and frankly, some that are not.

While sheltering at home, this might be a great time to explore your own strengths.

- Make a list of everything you did for your job in the last two weeks. I suspect that the list is different in light of the pandemic.

- Next to each activity write whether your loved it or loathed it.

- Add to the list other things you would enjoy doing but do not yet have the experience, education or ability to do.

- Chart your strengths on a simple four-quadrant graph:

- Once your activities are charted, think about actions you could take to allow more time for the activities that you do well and enjoy.

- Consider asking your co-workers to complete a similar exercise. You may find that you are doing things that you loathe that someone else might enjoy and do better than you.

You could also consider these questions:

- How would your board members react to charting their activities for your organization? Would they put more activities in the high energy/highly capable or the highly capable/draining quadrants?

- Do you think your donors would recognize things that they do for your organization as high energy/enjoyment?

- How about your volunteers and other constituents?

They say necessity is the mother of invention and right now we need leaders who not only understand their own strengths but can help their team members, co-workers, partners, and constituents leverage their strengths during these stressful times.

They’ll be stronger, you’ll be stronger, and our world will be stronger as a result.

KRISTINA CARLSON, CFRE

Managing Director, Carter Global

For more than 30 years, Kristina Carlson, CFRE has guided nonprofit institutions in their efforts to secure major gifts and other resources necessary to make a significant impact. She is a proven leader, an entrepreneur, an author of the best-selling Essential Principles for Fundraising Success, and an in-demand speaker at national and international conferences and workshops. As Managing Director with Carter, Kristina works to inspire philanthropists, volunteers, nonprofit leaders, and development professionals to do more by defining and focusing on mission-critical activities, creating systems of accountability, and experiencing the joy of philanthropy.

Feeling Unprepared for Your Capital Campaign?

I attended a fundraising conference where a friend and fellow fundraising consultant presented a session on the 15 essentials to launch a capital campaign. The title made my heart skip a beat. Running a thriving fundraising program while trying to orchestrate a multi-million-dollar capital campaign can be so stressful. I had to learn more, so I tracked my colleague down.

After exchanging updates on family and business, I asked how he came up with so many requirements. His response, “They wanted me to talk for three hours, so I came up with 15 to fill the time.”

Funny, I thought, the amount of work needed for a successful campaign depends upon how much time your consultant has to speak?? The idea of 15 essentials is more than enough to instill panic in the minds of busy Development Directors! I imagined participants giving up before they even got started.

Capital campaigns emerged more than 100 years ago in the United States and are growing around the globe. There is no shortage of opinions about what is needed to be successful. A simple Internet search results in any number of essentials, but 15 was the most I’ve ever seen.

Since 1989, I’ve helped lead hundreds of capital campaigns and from experience, I can confidently say the essentials boil down to five. That’s right, I’ve found the following “essentials” at the core of most successful campaigns:

- LEADERSHIP

Both institutional and volunteer leaders who will be actively involved in the campaign are needed to validate and share the campaign’s purpose with others. - COMPELLING AND EMOTIONAL CASE FOR SUPPORT

The needs that are articulated in your Case for Support must be extremely compelling and emotional. The Case must clearly demonstrate that a campaign is absolutely necessary to ensure that your organization can realistically achieve something important (change lives, change the world, etc.). Constituents will take your campaign seriously when they are convinced that the need is valid, urgent, and compelling. - ADEQUATE RESOURCES

Organizing volunteers, meeting with donors, preparing materials, and guiding a campaign take time. You must have adequate internal resources to conduct a successful campaign. Resources include people, systems, processes, volunteer support, and a campaign budget. - A GREAT PLAN

Every campaign has just one opportunity to be executed properly. Creating the proper leadership structure, a timeline with measurable milestones, and a strategy for early campaign momentum are imperative parts of a great plan. - SUFFICIENT CONTRIBUTABLE DOLLARS

Obviously, sufficient contributable dollars must be available to achieve success. Therefore, you must be certain that the number of prospects needed to ensure success exists and that the proper proportion of prospects relative to capacity is available.

While I believe in the importance of these five, I have often seen campaigns succeed without strength in each area. Curious to know if my experience mirrors others, I reached out to more than a dozen experienced capital campaign consultants to get their thoughts. Here is what they confirmed:

First, very few organizations start their campaigns with all five essentials in place. Most have to “build the bicycle while they ride it.”

Second, if leadership is not in place at the start of a campaign, it is the most difficult essential to obtain.

Third, as the chart below shows, the experts consider leadership to be the most critical with a compelling Case for Support coming in second. As one noted, “Excellent leadership has the potential to obviate other deficits.”

If you have leadership at the beginning, it indicates that people with passion and capacity believe strongly enough in the need to use their resources to influence others to get involved. The remaining essentials can evolve. For example, the Case may not be articulated perfectly at the beginning but can develop along the way. And, part of a great plan can include how you’ll manage the campaign until “adequate resources” are in place. But if you don’t have great leadership from the start, you will be hard-pressed to get the campaign out of the starting gate.

None of the experts considered adequate resources to be the most important. As one noted, “So far, every development team I’ve observed has been understaffed and under-budgeted for campaign work.”

How strong of a difference can leadership make? I once worked with an organization that had very little experience with philanthropy and the Executive Director had no interest in the campaign. She just wanted the money to help expand their services. The Board was not a “fundraising board” and very few donors supported the organization outside of buying tickets to events. However, one passionate and generous volunteer so loved the work of this organization that she went “all in” to make it a success. Not only did she make a very generous gift, she also met with at least one, more often two, donors a week throughout the duration of the campaign. As a leader, she almost single-handedly put the campaign over goal, and in the process deepened donor engagement and relationships.

With so much importance placed upon leadership, and knowing that most organizations must focus limited resources on the most critical activities, here is a list of suggested campaign readiness activities:

- Internal Leadership – Begin educating your organization’s executive team (CEO, CFO, etc.) about campaigns and the importance of a strategic plan and vision. The most successful campaigns are always rooted in a shared vision among the Board and staff, so make sure your internal leadership has spent time on this before campaign discussions begin.

Consider sharing this blog post with your team so they understand how critical their involvement is. Ask for their help in guiding a process to identify priorities, create a budget, and show the impact of contributed dollars on the organization’s mission. Develop a practice of having monthly meetings to discuss campaign readiness, key donor relationships, and next steps. Help your team become more comfortable with the fund development process by involving them in meetings to thank donors, answer their questions, and share the strategic vision with them.

- Board Leadership – Work with a Board committee, such as Governance, to evaluate your Board’s current strengths, particularly as it relates to fundraising, and develop a plan for putting in place the strongest possible Board. Engage the committee in regular meetings to discuss leadership identification, recruitment, Board training, and next steps. Ask the committee to make sure every Board member can easily articulate the organization’s mission and why it is personally important to them.

- Donor Leadership – Identify three to five people who could make significant gifts to the campaign and who could influence others to give as well. Create a plan for building relationships with these individuals. Note, I did not say create a plan for asking them for a campaign gift (at least not yet). Involve them in discussions about the ideas for the campaign, with a focus on the impact a campaign could have on the lives of individuals, the community, and the world. Share their feedback with your organization’s leaders.

There is always more you could do to prepare for a campaign, but don’t let that paralyze your organization. Prioritize your focus on developing leaders, volunteer and professionals, who are passionate, determined, and have confidence in the unlimited potential of your organization. In the words of Teddy Roosevelt, attract leaders who “believe you can, and you are halfway there.”

KRISTINA CARLSON, CFRE

Managing Director, Carter Global

For more than 30 years, Kristina Carlson, CFRE has guided nonprofit institutions in their efforts to secure major gifts and other resources necessary to make a significant impact. She is a proven leader, an entrepreneur, an author of the best-selling Essential Principles for Fundraising Success, and an in-demand speaker at national and international conferences and workshops. As Managing Director with Carter, Kristina works to inspire philanthropists, volunteers, nonprofit leaders, and development professionals to do more by defining and focusing on mission-critical activities, creating systems of accountability, and experiencing the joy of philanthropy.

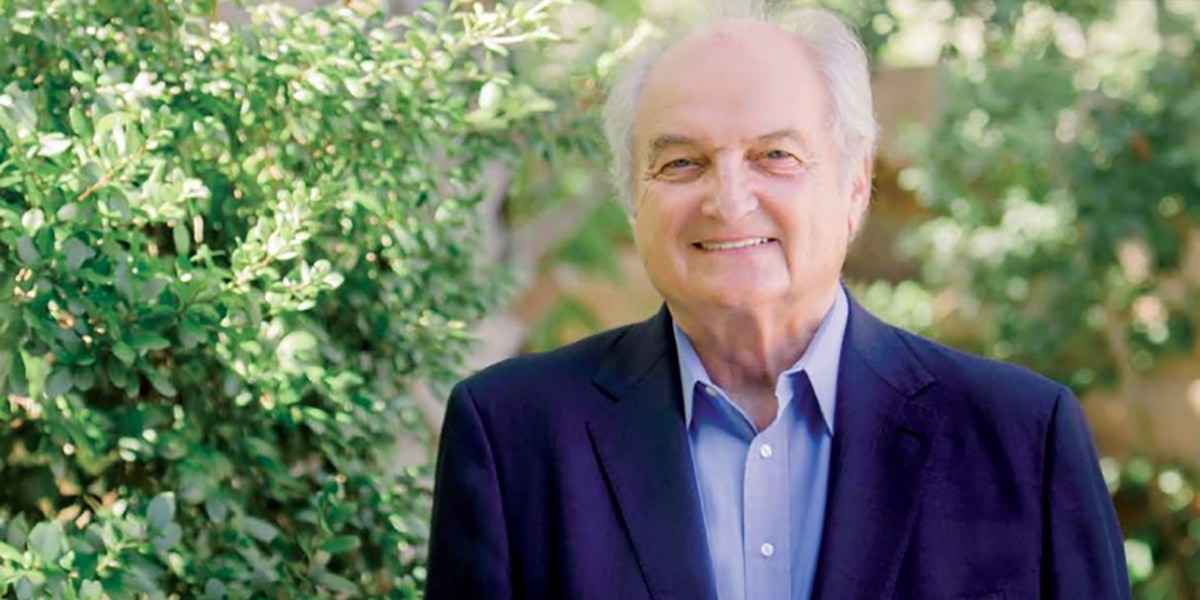

Deep Roots In Philanthropy

Philanthropy is so deeply rooted for Bob Carter that his volunteerism and career have melded into a life devoted to helping charitable organizations worldwide. While his classmates at Johns Hopkins University were electing careers in medicine and on Wall Street. Carter began teaching British and American literature. He was drawn into fundraising-eventually for his alma mater and then for Ketchum where he spent 15 years as President and CEO of its fundraising arm. Carter’s “retirement” lasted less than three months, and he founded his namesake firm, Carter, in 2011.

The company has grown to 30 professionals, each with less than 15 years’ experience, who work locally, nationally, and internationally, helping nonprofits with fundraising, governance, and strategic planning. Carter has aided West Coast Black Theatre Troupe’s capital campaign, Sarasota Ballet, Boys and Girls Clubs Manatee County, and is working with the Van Wezel Foundation’s performing arts center bayside. Carter has chaired seven nonprofit boards, including Mote Marine Laboratory’s board on which he still serves. He currently is volunteering with a committee to establish a foundation that will allow the World Health Organization to receive funding through private donations for the first time. Another project involves raising funds for a new university in Switzerland alongside a Russian entrepreneur.

Carter has received many awards throughout his career, inducing being named a Rotary Club Paul Harris Fellow. A gifted athlete who helped take Johns Hopkins’ lacrosse team to two Division I championships, Carter was a three-sport athlete at The Boys’ Latin School, which honored him as an Outstanding Alumnus. He and his wife, Carol, past Vice-Chancellor at the University of Pittsburgh, are both active in international and local philanthropy, and she now serves as an Anna Maria Island commissioner.

– used with permission from SARASOTA SCENE magazine

Nonprofit Expert Bob Carter Shares His Tips For Choosing a Charity

Beyond its award-winning beaches and abundant cultural attractions, Sarasota County has one more claim to fame. It’s overflowing with nonprofit organizations – 2,154 of them, according to the Florida Nonprofit Alliance- making it among the top two or three counties in the entire U.S. for the number of nonprofits per capita.

That’s from Bob Carter, chairman of Sarasota-based Carter, whose 30-member team of consultants advises some four dozen nonprofits each year around the world on strategic planning, governance and fund-raising campaigns – everything from the Westcoast Black Theatre Troupe’s recent $8 million Heart & Soul campaign to World Vision U.S.’s current $1 billion Every Last One campaign to eradicate extreme poverty across the globe.

That’s from Bob Carter, chairman of Sarasota-based Carter, whose 30-member team of consultants advises some four dozen nonprofits each year around the world on strategic planning, governance and fund-raising campaigns – everything from the Westcoast Black Theatre Troupe’s recent $8 million Heart & Soul campaign to World Vision U.S.’s current $1 billion Every Last One campaign to eradicate extreme poverty across the globe.

That Sarasota ranks so high is a dubious honor, he points out, because there’s so much duplication of missions and programs here, and such heavy competition for philanthropic dollars.

So, with more than 2,100 choices – not to mention the 1,368 nonprofits in neighboring Manatee County – what’s a newcomer to our area, or a recent retiree with time on his hands, or a professional who wants to burnish her C.V. to do when they want to apply their knowledge, skills and dollars to help a local nonprofit?

“Giving is 90 percent emotional and 10 percent rational,” says Carter, who is chair-emeritus of the Association of Fund-Raising Professionals international board of directors. But there are measurements to guide you.

There’s lots of chatter about fundraising in 2019:

I can’t resist putting my take on it. It’s a result of weathering 5 recessions etc. etc! Here goes:

The best fundraisers will be successful if:

They will use the tools available in technology with applied analytics and continue to develop strong relationships with top prospects for major and mega gifts.

They will not spend time talking about the tax laws but will recognize that cases for support have always overcome tax changes.

They will treat all gifts as noble and donors as having the potential to grow their gifts if given opportunities that excite them to do so.

They will make sure their cases are relevant, urgent and emotional, remembering that giving is 90% emotional and 10% rational.

It’s all about human behavior. We should all remember that the appreciation in the USA equities market is extremely significant as it sat at 6,500 in March of 2009 and now we worry about a 100 to 200 point slide from 25,000 to 23,000 or more. Most major donor prospects today have been investing and captured that growth for the last decade. fundraising drivers: equities and employment In other words, 2019 will be what you make it. Pick up your phone, get out from behind the desk and remember that no fundraising happens at your desk!